Rocky Mountain MIRECC TBI Toolkit

Jump to: Substance Misuse/Abuse | Depression | Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) | References

Co-Occurring Mental Health Disorders

The relationship and co-occurrence of mental health issues, substance use disorders, and TBI is well-documented (Corrigan and Deutschle, 2008). While assessment and treatment of TBI frequently focus on physical or cognitive impairment, psychological and psychosocial difficulties account for causes of disability (NIH Consensus Development Panel on Rehabilitation of Persons with TBI, 1999). Premorbid psychiatric symptoms may impair an individual’s cognitive and psychosocial functioning (Rapoport, McCullagh, Streiner, and Feinstein, 2003; Rosenthal, Christiensen, and Ross, 1998) and may be further exacerbated post injury. It may be helpful for clinicians to discuss if and how the individual’s TBI history and associated symptoms are impacting co-occurring problems. While there are many co-occurring mental health concerns among Veterans with TBI history, we will focus specifically on substance misuse/abuse, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The relationship and co-occurrence of mental health issues, substance use disorders, and TBI is well-documented (Corrigan and Deutschle, 2008). While assessment and treatment of TBI frequently focus on physical or cognitive impairment, psychological and psychosocial difficulties account for causes of disability (NIH Consensus Development Panel on Rehabilitation of Persons with TBI, 1999). Premorbid psychiatric symptoms may impair an individual’s cognitive and psychosocial functioning (Rapoport, McCullagh, Streiner, and Feinstein, 2003; Rosenthal, Christiensen, and Ross, 1998) and may be further exacerbated post injury. It may be helpful for clinicians to discuss if and how the individual’s TBI history and associated symptoms are impacting co-occurring problems. While there are many co-occurring mental health concerns among Veterans with TBI history, we will focus specifically on substance misuse/abuse, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

To learn more about Veteran mental health and TBI, view the RAND Corporation’s report: “Invisible Wounds: Mental Health and Cognitive Care Needs of America’s Returning Veterans”

To learn more about Veteran mental health and TBI, view the RAND Corporation’s report: “Invisible Wounds: Mental Health and Cognitive Care Needs of America’s Returning Veterans”

Substance Misuse/Abuse

Jump to: Background | Screening | Assessment | Intervention

Background Information

Problems with drinking or substance use may occur in response to stress or in combination with PTSD, depression, or other mental health and medical conditions. Pre-injury alcohol and drug abuse increases the risk for sustaining TBI (Vassallo et al., 2007). Additionally, clients with a history of substance abuse often have worse outcomes after sustaining a TBI (Corrigan, Rust, & Lamb-Hart, 1995). Substance use disorders typically decrease after an initial TBI, but there is usually an increase in substance use approximately two to three years after the TBI (Kreutzer, Marwitz & Witol, 1995). Substance use poses an increased risk for future TBIs.

It is essential for providers to routinely assess substance use in the ongoing management of individuals who sustained a TBI.  The video “Substance Use and Traumatic Brain Injury Risk Reduction and Prevention“ may be helpful for you and your client to view together in practice. The video provides education on how substance use can influence a person with TBI, the risks associated with substance use after a TBI, and how to reduce risk from sustaining future injuries. This video was designed to open dialogue with clients on the topic of substance use.

The video “Substance Use and Traumatic Brain Injury Risk Reduction and Prevention“ may be helpful for you and your client to view together in practice. The video provides education on how substance use can influence a person with TBI, the risks associated with substance use after a TBI, and how to reduce risk from sustaining future injuries. This video was designed to open dialogue with clients on the topic of substance use.

BrainLine provides more information about substance use and TBI at their website.

BrainLine provides more information about substance use and TBI at their website.

The Ohio Valley Center for Brain Injury Prevention and Rehabilitation (OVC) also provides useful information about working with individuals with TBI and substance use disorders.

The Ohio Valley Center for Brain Injury Prevention and Rehabilitation (OVC) also provides useful information about working with individuals with TBI and substance use disorders.

Another relevant article is Substance Use and Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Risk Reduction and Prevention: A Novel Model for Treatment co-authored by Jennifer Olson-Madden.

Screening

As a provider caring for a Veteran with a history of TBI, treatment planning should incorporate various assessments, screenings, and diagnostic tools. It is important to use valid and reliable tools that are tailored to best meet the need of the client living with TBI.

Remember that screening tools are brief, standardized tools used to capture a quick picture of the client at one point in time to see if further evaluation is needed.

Example of tools to use to screen for substance use in clients with a history of TBI

One of the pitfalls of using standardized screening tools in practice is that they may not be appropriate for patients with a history of TBI. Two screening and assessment tools to consider that have been tested and determined to be valid measures for individuals living with TBI are:

One of the pitfalls of using standardized screening tools in practice is that they may not be appropriate for patients with a history of TBI. Two screening and assessment tools to consider that have been tested and determined to be valid measures for individuals living with TBI are:

AUDIT-C (brief Alcohol Screening Questionnaire for Unhealthy Alcohol Use)

The AUDIT-C is a 3-item alcohol screen that can help identify persons who are hazardous drinkers or have active alcohol use disorders (including alcohol abuse or dependence). It does not include drug use.

| AUDIT-C | |

|---|---|

| The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test is a publication of the World Health Organization, @ 1990 | |

| Q1: How often did you have a drink containing alcohol in the past year? | |

| Answer | Points |

| Never | 0 |

| Monthly or less | 1 |

| Two to four times a month | 2 |

| Two to three times a week | 3 |

| Four or more times a week | 4 |

| Q2: How many drinks did you have on a typical day when you were drinking in the past year? | |

| Answer | Points |

| None, I do not drink | 0 |

| 1 or 2 | 0 |

| 3 or 4 | 1 |

| 5 or 6 | 2 |

| 7 to 9 | 3 |

| 10 or more | 4 |

| Q3: How often did you have six or more drinks on one occasion in the past year? | |

| Answer | Points |

| Never | 0 |

| Less than monthly | 1 |

| Monthly | 2 |

| Weekly | 3 |

| Daily or almost daily | 4 |

| The AUDIT-C is scored on a scale of 0-12 (scores of 0 reflect no alcohol use). In men, a score of 4 or more is considered positive; in women, a score of 3 or more is considered positive. Generally, the higher the AUDIT-C score, the more likely it is that the patient's drinking is affecting his/her health and safety. | |

DAST-10 (Drug Abuse Screening Test-10)

The DAST-10 is a 10-item, yes/no self-report instrument that has been condensed from the 28-item DAST and should take less than 8 minutes to complete. The DAST-10 was designed to provide a brief instrument for clinical screening and treatment evaluation and can be used with adults and older youth.

Download the DAST-10 from the SAMHSA website

Assessment

Diagnostic Assessment:

Comprehensive Addiction and Psychological Evaluation (CAAPE)

CAAPE is a comprehensive tool that can be used for diagnostic purposes as part of a routine clinical intake when both substance use disorders and mental health disorders need to be considered. It takes approximately 35-50 minutes to complete the evaluation.

CAAPE is a copyrighted instrument. For purchase information, visit Evince Clinical Assessments

Symptom Severity Assessment:

The Brief Addiction Monitor (BAM)

The BAM is a 17-item assessment that can be administered by a clinician or completed as a self-administered questionnaire for clients involved in outpatient substance abuse programs. It includes both symptom level outcomes as well as functional outcomes.

Intervention

Interventions for substance misuse/abuse should be symptom-focused and evidence based in concurrence with current practice guidelines.

The VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines on Substance Use Disorders can be found at their website along with the full guideline and a pocket guide.

Depression

Jump to: Background | Screening | Assessment |Intervention

Background Information

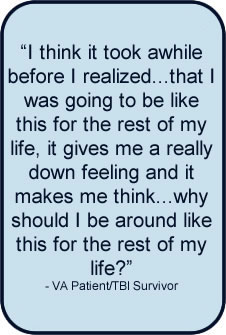

Individuals who have sustained a TBI are at higher risk for depression than the general population (Hibbard, et al., 1998). The risk of depression after a TBI increases whether the injury is mild, moderate, or severe. Research by Bombardier and colleagues suggested that 53% of individuals hospitalized for complicated mild to severe TBI met criteria for major depressive disorder during the first year after TBI (Bombardier et al., 2010). In addition, symptoms of depression among individuals who have a history of TBI have been described as existing on a continuum that may fluctuate over time (Hart et al., 2012). For example, clients who are experiencing a minor depression who do not receive treatment are at risk of developing major depressive disorder (Hart et al., 2012).

Individuals who have sustained a TBI are at higher risk for depression than the general population (Hibbard, et al., 1998). The risk of depression after a TBI increases whether the injury is mild, moderate, or severe. Research by Bombardier and colleagues suggested that 53% of individuals hospitalized for complicated mild to severe TBI met criteria for major depressive disorder during the first year after TBI (Bombardier et al., 2010). In addition, symptoms of depression among individuals who have a history of TBI have been described as existing on a continuum that may fluctuate over time (Hart et al., 2012). For example, clients who are experiencing a minor depression who do not receive treatment are at risk of developing major depressive disorder (Hart et al., 2012).

Many factors contribute to the causes of depression following a TBI, including:

- Physical changes in the brain due to injury to the areas of the brain that control emotions, or changes in the level of neurotransmitters;

- Emotional response to injury due to adjustment issues and role changes;

- Factors unrelated to the injury, such as personal or family history that were present before the TBI

Source: Depression after Traumatic Brain Injury — Download

![]() The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's (AHRQ) and it's Effective Health Care Program has produced a summary report of research findings related to TBI and depression that is available here for download.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's (AHRQ) and it's Effective Health Care Program has produced a summary report of research findings related to TBI and depression that is available here for download.

Screening

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a brief and easy-to-use screener for symptoms of depression based on DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. It has excellent internal and test-retest reliability as well as criterion and construct validity in medical samples. With regard to use in a TBI population, it has been found to have very high sensitivity (0.93) and specificity (0.89; Fann, Bombardier, Dikmen, Esselman, Warms, et al., 2005). The PHQ-9 has advantages as a depression screening tool in TBI populations given that it is short, can be administered via self-report or by non-clinician interview, and positive results can point both to possible diagnosis of major depression as well symptom severity.

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a brief and easy-to-use screener for symptoms of depression based on DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. It has excellent internal and test-retest reliability as well as criterion and construct validity in medical samples. With regard to use in a TBI population, it has been found to have very high sensitivity (0.93) and specificity (0.89; Fann, Bombardier, Dikmen, Esselman, Warms, et al., 2005). The PHQ-9 has advantages as a depression screening tool in TBI populations given that it is short, can be administered via self-report or by non-clinician interview, and positive results can point both to possible diagnosis of major depression as well symptom severity.

The PHQ-9 can be downloaded here

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) contains 21 items that are specifically designed to assess DSM-IV criteria for symptom severity of depression.

*Note: The BDI-II should be scored using a cut score of 19 for individuals with a mild TBI and 35 for individuals with moderate to severe TBI (Homaifar et al, 2009).

Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)

The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) contains 53 items to assess 9 dimensions (somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, psychoticism) plus three global indices: Global Severity Index, Positive Symptom Distress Index, Positive Symptom Total.

Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS)

The Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) contains 20 items to measure three aspects of hopelessness (feelings about the future, loss of motivation, and expectations). The BHS can also be used as an indicator of suicidal risk in individuals who are depressed and who have made suicide attempts.

Assessment

Symptoms of depression may be a common response to coping with the losses and challenges associated with a TBI. However, when symptoms persist for more than two weeks and a client screens positive on one of the screening measures, further assessment is indicated.

Diagnostic Assessments

Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (SCID) – Depression Module

The SCID is a semi-structured interview for making Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) Axis 1 diagnoses. It is divided into modules. The mood disorder module can be used to assess mood disorders, including major depressive disorder. The SCID development team has completed a final draft of the SCID for DSM-5 and is currently revising the User’s Guide. For more information, including ordering information.

Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)

The MINI is a short structured diagnostic interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10 psychiatric disorders. The entire tool can be administered in approximately 15 minutes, though the depression module can be used alone. For more information.

Symptom Severity Assessment

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) contains 21 items that are specifically designed to assess DSM-IV criteria for symptom severity of depression. Purchase the BDI-II here

*Note: The BDI-II should be scored using a cut score of 19 for individuals with a mild TBI and 35 for individuals with moderate to severe TBI (Homaifar et al, 2009).

Intervention

Interventions for depression should be symptom-focused and evidence based in concurrence with current practice guidelines.

Interventions for depression should be symptom-focused and evidence based in concurrence with current practice guidelines.

The VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines on Major Depressive Disorders can be found at their website along with the full guideline and a pocket guide.

The VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Concussion and Mild Traumatic Brain Injury also provides information regarding depression post-injury. It can be found at their website along with the full guideline and pocket guide.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Jump to: Background | Screening \ Assessment | Intervention

Background Information

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) can occur after a person is exposed to a traumatic event. PTSD often co-occurs with other mental health problems, such as depression, substance abuse, and TBI. PTSD is now categorized as a Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorder in the DSM 5. Visit this page for a complete description of the diagnostic criteria for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Also, review changes to the diagnosis from the DSM-IV-TR edition.

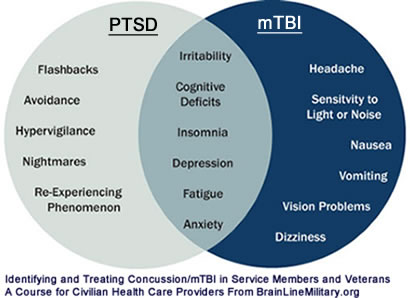

Separating symptoms of TBI and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a challenging process. The diagram below shows a sample of some common symptoms of PTSD and mild TBI.

According to Silver, Hales, and Yudofsky (1997), TBI symptoms typically tend to decrease within three to six months after the injury, whereas PTSD symptoms may last much longer. The Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury reports that education is the first step in treating anyone with PTSD. It is important for clients to be made aware of possible symptoms and the expected course of recovery. Many people who develop PTSD get better. However, approximately one in every three individuals with PTSD will continue to have symptoms.

The Health.mil:Traumatic Brain Injury provides information and tips for civilian providers regarding treating military members with TBI and PTSD.

The VA National Center for PTSD offers a number of videos related to recovery, treatment, and assessment as well as helpful materials for clinicians working with Veterans living with PTSD.

Screening

Recent studies have found increased rates of PTSD among individuals with a history of mild TBI (Bryant et al., 2010). This may be due to problems with emotional regulation, impaired cognitive strategies that make it more difficult for those with TBI to manage their emotional stress, as well as additional stressors that can occur after a TBI. Screening for symptoms of PTSD is an appropriate step to make in clinical practice for all clients who have a history of TBI.

Recent studies have found increased rates of PTSD among individuals with a history of mild TBI (Bryant et al., 2010). This may be due to problems with emotional regulation, impaired cognitive strategies that make it more difficult for those with TBI to manage their emotional stress, as well as additional stressors that can occur after a TBI. Screening for symptoms of PTSD is an appropriate step to make in clinical practice for all clients who have a history of TBI.

However, it can be difficult to get an accurate picture of the presence of PTSD symptoms in individuals who have a history of TBI.

There are a variety of tools that can be used to screen for PTSD in clients with a history of TBI. Below is an example of one such tool.

Short Form of the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version

The Short Form of the PCL is a 6-item screen that contains two items from each of the re-experiencing, avoidance, and hyperarousal symptom clusters. Those who screen positive should be assessed further with a structured interview to determine whether or not their symptoms meet criteria for PTSD. Please note that this screen uses the three symptom clusters from DSM-IV, not DSM-5.

Providers can obtain more information, including scoring and cutoff information, here

Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD)

The PC-PTSD is a four-item screen that can be used by primary care or in other medical settings. VA currently uses the PC-PTSD to screen Veterans for PTSD. Those who answer “yes” to at least three questions are considered to have a “positive” screen. These individuals should then be assessed for PTSD with a structured interview.

Providers can learn more about the Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD) here.

Providers can download the Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD) here.

Assessment

Diagnostic Assessment

Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSm-5 (CAPS-5)

The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale-5 (CAPS-5) is considered to be the ‘gold standard’ for assessing and diagnosing PTSD. The previous CAPS was updated to incorporate the DSM-V PTSD diagnostic criteria. The CAPS-5 is a 30-item structured interview that can be used to make a current or lifetime diagnosis of PTSD as well as to track PTSD symptoms over the past week.

- For information about the changes from the previous version of the CAPS.

- For training on the use of CAPS

- Clinicians may request a copy of CAPS here

Symptom Severity Assessments

PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)

- Download information about the PCL-5, including information about the changes from the previous PCL-5

- Master’s level providers may request a copy of the PCL-5

- Please note that the PCL-M has been updated to reflect the DSM-V criteria. The new measure has not yet been validated with individuals with a history of TBI.

Short Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Rating Interview (SPRINT)

- The Short Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Rating Interview (SPRINT) can be used to assess the core symptoms of PTSD. Using this tool on a regular basis with your client may allow you to evaluate how symptoms may be changing over time. Information for obtaining SPRINT is available on the National Center for PTSD website.

Intervention

Interventions for PTSD should be symptom-focused and evidence based in concurrence with current practice guidelines.

The VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines on PTSD can be found at their website along with the full guideline and a pocket guide.

The VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines on PTSD can be found at their website along with the full guideline and a pocket guide.

References

Bombardier CH, Fann JR, Temkin NR, Esselman PC, Barber J, Dikmen SS. Rates of major depressive disorder and clinical outcomes following traumatic brain injury. JAMA. 2010 May 19;303(19):1938-45.

Bryant, R., Creamer, M., O’Donnell, M., Silove, A., Clark, C., and McFarlane, D. (2010). The psychiatric sequelae of traumatic injury. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(3), 312-320.

Corrigan, J. D., & Deutschle, J. J. (2008). The presence and impact of traumatic brain injury among clients in treatment for co-occurring mental illness and substance abuse. Brain Injury, 22, 223–231.

Corrigan, J., Rust, E., Lamb-Hart, G. (1995). The nature and extent of substance abuse problems in persons with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 10(3), 29-46.

Fann, J.R., Bombardier, C.H., Dikmen, S., Esselman, P., Warms, C.A., Pelzer, E., Rau, H., & Temkin, N. (2005). Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in assessing depression following traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil, 20(6), 501 – 511.

Hart, T., Hoffman, J., Pretz, C., Kennedy, R., Clark, A., and Brenner, L. (2012). A longitudinal study of major and minor depression following traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93(8), 1343-1349.

Hibbard MR, Uysal S, Kepler K, Bogdany J, Silver J (Aug 1998). Axis I psychopathology in individuals with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 13(4), 24-39.

Homaifar, B., Brenner L., Gutierrez, P., Harwood, J., Thompson, C, Filey, C., et al. (2009). Sensitivity and specificity of the Beck depression inventory-II in persons with traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabilitation, 90(4):652–6.10.1016/j.apmr.2008.10.028

Kreutzer J., Marwitz, J., Witol, A. (1995). Interrelationships between crime, substance abuse, and Aggressive behaviours among persons with traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 9, 757-768.

McDonald, S. and Calhoun, P. (2010). The diagnostic accuracy of the PTSD checklist: a critical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(8), 976-987.

National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Panel on Rehabilitation. (1999). Report of the consensus development conference on the rehabilitation of persons with traumatic brain injury. Retrieved from here on August 20, 2014.

NIH Consensus Development Panel on Rehabilitation of Persons With Traumatic Brain Injury. (Sep 1999). Consensus conference. Rehabilitation of persons with traumatic brain injury. JAMA, 282(10), 974-83.

Rappaport, MJ, McCullagh, S, Streiner, D, Feinstein, A. (2003). The clinical significance of major depression following mild traumatic brain injury. Psychosomatics 44(1): 31-37.

Rosenthal, M., Christensen, B.K., & Ross, T.P. (1998). Depression following traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 79, 90-103.

Silver, J., Hales, R., & Yudofsky, S. (1997). Neuropsychiatric aspects of traumatic brain injury. The American Psychiatric Textbook of Neuropsychiatry, 3rd Ed. Edited by Yudofsky, S., Hales, R. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press, pp 521-560.

Vassallo J.L. Proctor-Weber Z. Lebowitz B.K. Curtiss G. Vanderplofg R.D. (2007). Psychiatric risk factors for traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 21:567–573.

Your Feedback

Your feedback is tremendously important to keeping this toolkit up to date and relevant. If you find broken links, out of date information, or you have questions, suggestions or quibbles please contact Joe Huggins at joe.huggins@va.gov.

Thanks!

Site Map

Contact Information

Denver

Rocky Mountain Regional VAMC (RMR VAMC)

1700 N Wheeling St, G-3-116M

Aurora, CO 80045

720-723-6493

Salt Lake City

VA Salt Lake City Health Care System

500 Foothill DR

Salt Lake City, UT 84148

801-582-1565 x2821